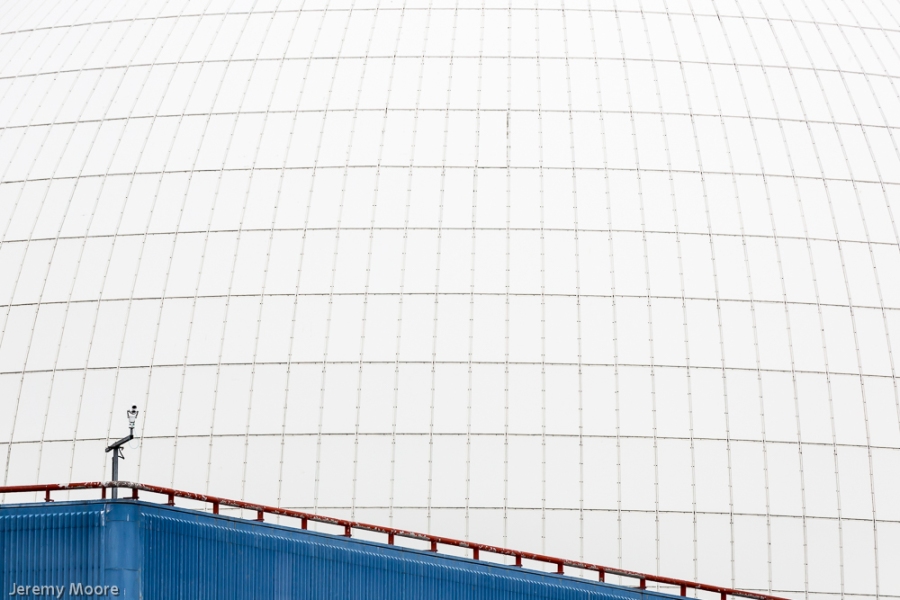

After an hour or so I turned my attention away from the kittiwakes offshore (see previous post) and re-assessed my surroundings. There was only one landscape feature to be seen – the brilliant white reactor dome of Sizewell B and the extensive blue-painted steel clad building upon which it rested. Red railings ran along the edge of the latter. Whatever your opinion on nuclear power, the clean lines and simple colour scheme of the power plant gave it a modernist and surreal splendour. Far more attractive than the crumbling and filthy concrete of Sizewell A alongside it.

And wait, there was a black-backed gull resting on the railings in front of the dome! This was an opportunity not to be missed! I grabbed my tripod and stumbled across the shingle: the bird could leave at any time. I left the focal length at 600 mm to isolate the scene from its few surroundings and took a small selection of exposures over the next minute or so until the bird flew. Such an extreme focal length would flatten the scene substantially and result in a very limited depth of field, so I set apertures of f13 or f16 and added a stop or two of exposure to correct for the largely white subject.

Until this moment I wasn’t sure I would return from this trip with any worthwhile results. It had been quite a while since I had been “in the zone” but I felt I was there now. I remembered a comment from the late lamented landscape photographer Fay Godwin after she had spent ten days in northern Scotland. She thought she might have returned with “one very good photograph”. I could identify with that. As I left I felt sure I would be approached by power station security; after all – who but a terrorist would want to photograph a nuclear power plant? But as it happened my imagination was running amok.

I returned to Sizewell the next morning in the hope that I could repeat the image. Almost all the kittiwakes had left the tower and it was over two hours before a gull landed on the railings again. But while I waited I began to see the structure without the bird as pure landscape. A security camera on a post took the place of the gull and gave the image a focal point. Not everyone will like it but I think it works.

So rather than the one good image that I thought I might come back with there are actually several. It’s funny how the most inspiring photography sessions can be the most unexpected.

To follow Tales from Wild Wales, scroll right down to the bottom of the page and click Follow